Read more about the Discovery Expedition

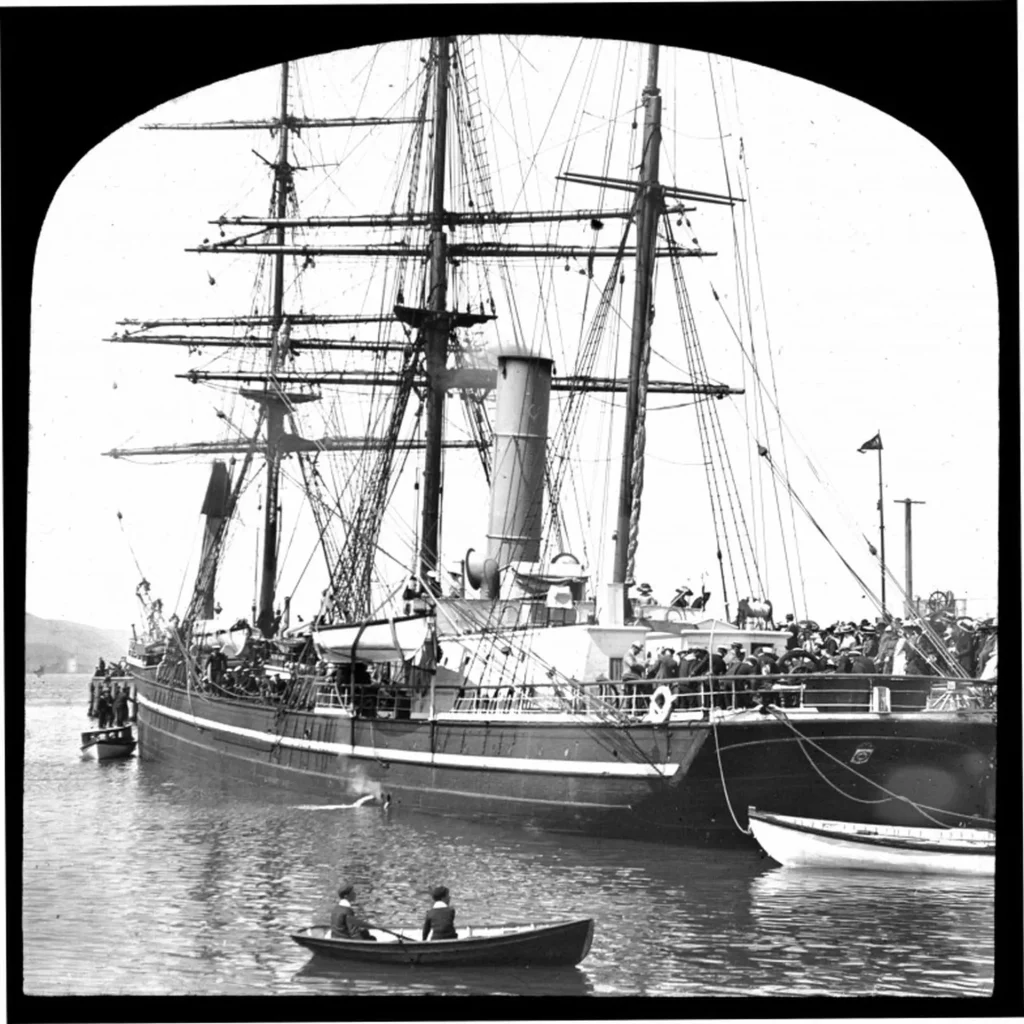

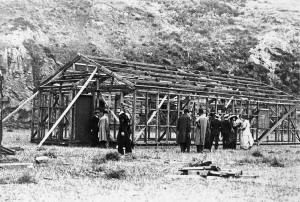

| The Discovery Expedition embarked from the Isle of Wight on 6 August 1901 sailing via the Cape of Good Hope to New Zealand and arriving in Antarctica at the Ross Barrier (a permanent ice shelf) where Scott landed on 4 February 1902, ultimately setting up base camp on a rocky promontory with huts for storage of their equipment while the men continued to live aboard Discovery. In sunless wintry conditions during May-August scientific research proceeded while Scott allowed Discovery to become ice bound for the duration of the Antarctic winter. Lashly commented that it was ‘a dreary place’. Discovery arrived back in Portsmouth on 10 September 1904 and public enthusiasm soon followed with Scott promoted to Captain and entertained by King Edward VII at Balmoral. Scott was given leave by the Navy to write his account of the expedition and it was published in 1905 as The Voyage of the Discovery, with impressive sales. Scott wrote a separate report to the Admiralty, singling out Lashly and Evans in glowing terms: “I would remark that I think that journey nearly reached the limit of performance possible under the conditions, in order to point out that it could not have been accomplished had either of these men failed in the smallest degree. Their determination, courage, and patience were often taxed to the utmost, yet I never knew them other than cheerful and respectful. On one occasion Lashly undoubtedly saved our lives by his presence of mind when Evans and I had fallen into a crevasse”. |  Discovery moored by the Barrier ice shelf

Shackleton, Scott and Wilson pictured on their return from their Polar trek on 3 February 1903. The effects of weather and ice made them almost unrecognisable to the crew. |

| The Discovery crew were paid off and given two months leave and in recognition of their service all expedition members were awarded the Polar Medal. Lashly was promoted to Chief Stoker and went to the Royal Naval College at Osborne, Isle of Wight, as an instructor to Officer Cadets, however it was not long before he returned to sea, serving on HMS Proserpine patrolling the Persian Gulf. Tom Crean was promoted from Able Seaman to Petty Officer. | |

Above: Scott’s Hut at Cape Evans as it is today – (Kuno Lechner photographer)

From The Hambledonian, October & November 2012 – Article by Christine Trickett, relative of William Lashly and Hambledon resident

This being the centenary of Captain Scott's ill-faced expedition to the Antarctic, I thought it appropriate, and perhaps of interest to new residents, to write a little about William Lashly, a crew member on both the Discovery and the

Terra Nova.

He was born in Hambledon on Christmas Day, 1867, the son of a thatcher. After attending the village school, he started working for his father. At the age of 21, William joined the Navy as a Stoker. He married in 1896 and his daughter, Alice, was born four years later. In 1901, Lashly was one of the Naval volunteers chosen for the Discovery expedition to Antarctica. He was described as a quiet sort of man who knew his job backwards, a teetotaller and non-smoker.

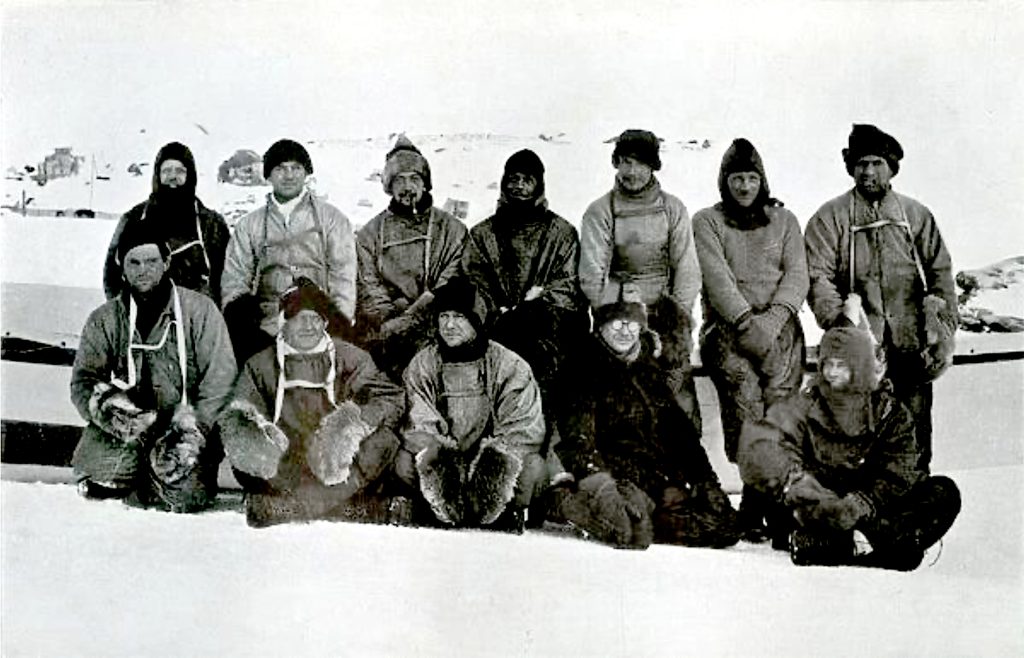

After the ship's return to England in 1904, he was promoted to Chief Stoker and went to the Royal Naval College at Osborne as an instructor to the Officer Cadets. Having proved his worth many times, William Lashly was a natural choice for Captain Scott's last expedition, and he joined the Terra Nova in the spring of 1910. Despite being in the last supporting party, Lashly was not selected by Captain Scott for the final push to the Pole in January 1912. It has since been said that if he had been taken, the whole story might have been different.

When the sledging season came around in October of that year, he was in the search party that found Captain Scott and his two companions. Lashly was taken into the tent by the Royal Naval surgeon because he was the oldest of them all and one of the last to have seen Scott and the missing members of the Polar party. When he came out he was visibly upset but said nothing. Upon their return to England in 1913, Lashly and Petty Officer Crean were awarded the Albert Medal for saving the life of Lieutenant Evans during their return to Base Camp. It is recorded that he visited Hambledon School in August of that year and spoke graphically to the older children of life in high latitudes, before showing them his medal.

After taking his pension, Lashly joined the Royal Fleet Reserve and in 1915 survived the sinking of HMS Irresistible in the Dardanelles campaign. He finally took up employment with the Board of Trade in Cardiff. In 1932 he returned to Hambledon and built a house, which he called Minna Bluff after a familiar Antarctic landmark. William Lashly travelled around the area, speaking and showing magic lantern slides. He explained to the Gosport Brotherhood on one such occasion, that when he first volunteered for the expedition he was asked whether he could sing, dance or play an instrument. His reply was 'You have not asked me whether I can work!' He also said 'A month was long enough to wear a shirt without turning it. You would not believe the comfort you get out of a shirt that has been turned!' He also commented that people often asked why he went on such expeditions, and his reply was 'What should we know if we did not go adventuring?'

He died and was buried in Hambledon in 1940, at the age of 73. It was his express wish that there was to be no headstone on his grave. My aunt, Edith Lashly and I were invited to the opening of Lashly Meadow in 1993. My grandfather was William Lashly's cousin.

Christine Trickett

West Street, Hambledon

From The Hambledonian, December 2012 & January 2013 – Article by Nick Bailey, William Lashly – An Appreciation

In the last issue of The Hambledonian Christine Trickett wrote a splendid profile of her famous relative Chief Stoker William Lashly, who had accompanied Captain Scott on both of his expeditions to the Antarctic. Her grandfather was a cousin of William Lashly. This is the Centenary year of Captain Scott's Last Expedition to the South Pole in 1912 and it is regrettable that the lower Deck members of the expedition have been so neglected. Only Petty Officer Edgar Evans, who died on the return journey, has been remembered.

Among the neglected is our famous citizen William Lashly. He has been almost wholly forgotten. To Help us remember him better I have reprinted below the 'Appreciation' of William Lashly written at the time of his death in 1940 and included in the Polar Record of that year. It was written by Apsley Cherry-Garrard, a companion on Scott's Expedition, and the author of the famous book The Worst Journey in the World. It really brings William Lashly to life.

''Lashly is dead. He was a Chief Stoker in the Navy and he was one of the last survivors who Served on both of Scott's Antarctic expeditions. Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Titus Oates, Atkinson and Wild - all are gone; and Crean who died about a year ago, and Pennell as good as any of them.

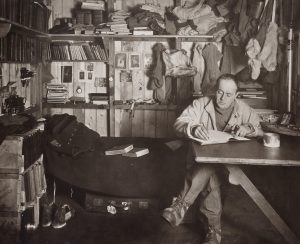

On the Discovery Lashly was one of Scott's companions who travelled westward over the newly discovered plateau. On the Last Expedition he was on the last supporting party. He saw the polar party as little black dots vanish into the southern horizon: and he did one of the longest man-hauling journeys on record, dragging a sick man part of the way.

Atkinson told me that he doubted if Lieutenant Evans could have lived another day, and that the best nurse in the world could have done no more than Lashly did. He had just brought him from the Barrier when I saw him. Crean helped him, that had not been man-hauling so long.

Lashly looked nothing out of the way till he was stripped. He stripped big and looked small: was tough as nails rather than muscular; and neither drank nor smoked. Behind that kindly smile, that half-filled the engine-room hatch on the Terra Nova, there were bottled up great reserves of quiet energy. He had much self-control; but he could burst like a sleeping volcano. He was good with animals, and the mules were left in his charge the last year down South. With them he came with us on the journey on which we found the bodies of the polar party. So now he lies at peace. No more facing the utmost physical toil, starvation and death together: no more knowing you can't go on and going on all the same: no more continual hunger awake or asleep; just peace.

When I was trying to write a book more than twenty years ago, I asked Lashly whether he could tell me anything about his journey back with the Last Return Party. He scratched his head and said he didn't know that he could, but he thought he had some old bits of paper with some notes on. He sent me a diary which must be known all over the world and one of my greatest difficulties when publishing it was to prevent the compositor altering the spelling. It ends - as he got into his sleeping-bag the evening the rescue party reached him: 'We are looking for a mail now. How funny we should always be looking for something else, now we are safe'.

So perhaps he is now looking for a good whack of pemmican: and still singing that cheery little ditty with which he used to end his day's work on earth."

Nick Bailey